NOVINKY

The parellels of spanish Flu and Covid19 on Hollywood

The year was 1918. As World War I was ending, the Spanish Flu began ravaging the world. Within a year, it killed 675,000 Americans and 50 million worldwide — 10 million more than those who perished in the war.

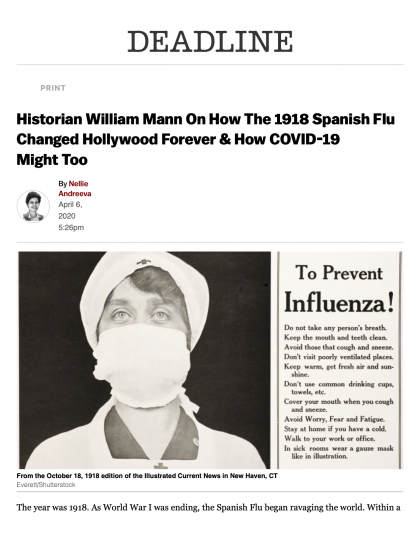

There are several parallels between the response to the Spanish Flu and COVID-19 in the U.S. In both cases, states of emergency were declared; all public places, including movie theaters and schools, were closed for months; and wearing face masks in public was recommended.

The Spanish flu pandemic brought about cataclysmic changes in the film business, most of them orchestrated by Adolph Zukor. It led to the establishment of the studio system, which continues to dominate Hollywood, and vertical integration, with studios wrestling control over movie theaters from mom-and-pop owners.

In an interview with Deadline, Hollywood historian William Mann, author of Tinseltown: Murder, Morphine, and Madness at the Dawn of Hollywood, which he and Kevin Murphy are adapting into a series for Spectrum Originals, talks about the Spanish flu pandemic’s profound impact on the film business, what big shakeups the current pandemic could bring (especially in theater ownership), and how long would it take for Hollywood to recover. He also points out mistakes made in handling the Spanish flu pandemic that today’s authorities should learn from, explains why the top film actors refused to wear masks in public back then, and acknowledges the biggest star Hollywood lost to the Spanish flu.

You can also follow a timeline of the 1918 epidemic in Hollywood under the Q&A that illustrates some of the points Mann makes and paints a fascinating picture of how the California and LA authorities tackled the crisis — sometimes winning, sometime stumbling — and how theater owners fought for survival.

DEADLINE: You have studied every chapter of Hollywood’s history. Why is this period, from about 1918 through about 1926, so important?

MANN: This is when Hollywood is created, this is when all of the structures that would define the American film industry were put into place — how movies were made, how they were sold, how they were shown.

This is the moment in history where the American film industry decided to go a particular way. Up to that point there were many different ways this could have gone, independent films, artists control — they tried that with United Artists. But the studio system was created in this period and it really begins with the 1918 epidemic.

DEADLINE: What role did the pandemic play in the creation of the studio system?

MANN: During the outbreak, between 80% and 90% of American movie theaters were closed for anywhere between two to six months. This was a huge disruption and not only moviegoing but movie-selling and moviemaking. It was patchwork across the country. New York and San Francisco held out for the longest time but eventually they had to shutter as well.

Los Angeles put out a ban pretty early on theaters. The studios — and this is when studios were both in Los Angeles and New York — put a ban on filming crowd scenes, and, to their credit, studios shut down all production during this period of time for well over a month, from the middle of October to the end of November of 1918.

First cases in L.A. were announced in September. About 3,000 people died in Los Angeles in a little more than a year, a quarter of all the deaths from that period. We forget how significant an impact this has had, and a lot of that was economic impact.

The studios had significant losses. Paramount lost nearly $2 million in 1918 to 1919; that’s more like $30 million now. Distributors also suffered because you can’t ship films when theaters are closed. But the greater economic impact was felt by the exhibitors, the mom-and-pop movie theaters across the country, which were ruined by this. A lot of them were living month to month, showing films and struggling to pay their bills, and when they suddenly were forced to close for two, three, four, six, seven months, they lost everything. Even after the theaters reopened, in many cases they didn’t come back until the middle part of 1919, so movie theaters were closing left and right.

The reality was at this point in time that American film exhibition was really mom and pop. It was small town, it was independent exhibitors. Some had formed a chain, some of them had formed associations, but for the most part it was not a huge control over the exhibition, and that’s where Adolph Zukor comes in. Because he had this idea way before the epidemic that if I could get control of all of these theaters, then I could control the entire industry, so he uses the epidemic to put that plan into place.

DEADLINE: How did he do that?

MANN: Zukor is a fascinating guy. He’s a villain but he’s also a guy with vision, and what he did put so many people out of business but at the same time created the American film industry, and it ran this way for the next 60-70 years. In some ways Zukor’s vision of filmmaking is still used today, even with new technologies; it’s the model of vertical integration, which means top-down control.

So Zukor said, here I am making movies, I should be able to then control how they’re distributed and then how they’re shown. By doing that, by taking control of all the aspects of the film industry, Zukor squeezed out all of these independent filmmakers, many of whom were women. He exploited the pandemic to build his new model in which women are cut out from positions of power, not to mention also people of color because there was a number of African-American and Chinese-American and Mexican-American filmmakers who were working in Los Angeles and had their own companies, had their own distribution networks. But when Zukor buys up everything, so many people lose access then and lose a voice in the industry.

Zukor wanted to do this all along but he saw this was the golden opportunity, and sends his lawyers out all across the country because he says he’s getting all these reports about theaters closing. He goes, “Oh, OK, so we just go out and offer them to take it off their hands.” And if they weren’t willing to sell for pennies on the dollar, say, “Well, I’m going to build another theater across the street and put you out of business.” They were tired, they were exhausted, they were losing money, and they just threw in the towel and gave in.

By 1921, Zukor, who was the head of what was called then Famous Players that becomes Paramount, was the biggest person in the industry. He controlled more theaters, he controlled more films, and he kept it that way for quite a long time.

DEADLINE: Looking now at movie theaters closing and what happened in 1918, how will the theater owners come out of the coronavirus pandemic?

MANN: I think it’s going to be really interesting. I think the COVID-19 closures could end up having as significant an impact on the movies as the 1918-19 influenza did. It will be different of course, but just as in 1918 the whole structure of the industry could change in a couple of years.

The cinema in 1921, just two years after the epidemic, was nothing like the industry from 1918, it had so radically changed. The length of the movies and the way people bought tickets for movies, all of this changed.

I look now at streaming services that now basically use Zukor’s model. They control production, distribution and exhibition. Zukor would be cheering them on. And yes, it does get some of the smaller people out of business, but there’s also ... it’s a very efficient model and maybe through this industry’s going to find another way in making sure that the product still gets out there.

DEADLINE: Instead of predominantly mom-and-pop-owned theaters we have mainly theater chains today. Will that factor into what happens to them or will it be just bigger players getting out of business? Who do you think in a couple years will own those theaters and will they remain relevant in the era of streaming?

MANN: Everybody’s asking the question now, are we ever going to go back to the movie theaters? This has been almost a couple of decades now as movies have become hard to do for particular audiences, and smaller movies have moved over to Netflix or to Amazon.

It’s hard to say that, because Zukor in 1918 saw the problem and exploited it, both for his own ends, but I also think for the good of the American film industry. I think that could happen here now. I don’t know who owns these movie theaters, will it be streaming companies, will it be somebody else, studios? I don’t know, but clearly there’s going to be some kind of a change.

DEADLINE: Any other parallels between the COVID-19 and the Spanish flu pandemic? On a local government level, the response is pretty similar, through in 1918 it seemed more chaotic, with a lockdown imposed, lifted and then enforced again multiple times. What is different this time, specifically here in California and Los Angeles?

MANN: Yes, you hit the nail on the head: Oftentimes these closings were lifted in 1918 way too soon. People were still dying of this in March and April and May of 1918. Mary Pickford, who was the biggest movie star of the time, she gets it in early 1919, so the movie theaters would reopen and nobody would come and then they’d close as the death rate continued to climb.

There needs to be a greater consistency — there is understanding, hopefully, that we’ve learned from 1918. You don’t do that, you keep the social distancing as long as you can. They didn’t use that word back then but I hope we learned, don’t repeat those mistakes.

DEADLINE: One of the mistakes we appear to have repeated is to not have enough face masks.

MANN: Yes, one of the things that was interesting to me as I was reading through this material several years ago when I was researching the book, but then again more recently when COVID hit, was the shortage of masks. People didn’t have enough masks, and then when people did get masks, it was seen as kind of cowardly — you’re a weakling if you’re going to wear a mask. Some of the biggest Hollywood stars would deliberately not wear masks in public because they didn’t want to appear, especially the men, they wanted to appear manly and masculine and you know, to wear a mask it was going to show that he’s weak.

DEADLINE: What were the best known Hollywood victims of the 1918 pandemic? Many of the biggest stars were fortunate and recovered.

MANN: Yes, a lot of them did recover. Mary Pickford recovered, Lillian Gish recovered. Both of them were huge, huge stars. But the biggest name in Hollywood who died was an actor by the name of Harold Lockwood. Nobody remembers him today sadly, but he was a really terrific actor. He worked for Metro which later becomes Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer and he was young, I think only about 31 years old. Very handsome, leading man, and he gets sick and dies within a few days. It’s shocking to the industry, and the fans are devastated.

DEADLINE: We are three weeks into the mass Hollywood shutdown. Studios are hoping to restart filming in the summer. Based on the events in 1918, when do you realistically think Hollywood will go back to normal?

MANN: It’s so hard to say. I mean, Hollywood in 1918 didn’t go

back to normal for at least another year. It took that long to

recoup their losses and to get everything reopened. We don’t really see the movie business pick up again, the slump doesn’t end until the end of 1919, clearly into 1920. So it’s hard to say how long this one will take. I hope the measures we’ve taken now have been more consistent and hopefully it won’t take us that long to recover from this, but clearly there’s going to be some economic pain all across the country.

1918 Spanish Flu and Hollywood

Date

Mid-September, 1918 Soldiers returning from WWI become first known Spanish flu infections.

September 22, 1918 Civilian cases start to appear; LA Mayor Frederick Woodman creates medical advisory board as health commissioner Dr. Luther Milton Powers warns the city should prepare for worst./

October 11, 1918 Woodman declares state of emergency; all public places are closed.

Shooting of crowd scenes is banned; Hollywood and east coast studios shut down film production for 3-4 weeks

October 12-14, 1918 City registers 300 cases and 11 deaths. Powers worngly assumes epidemic has peaked.

October 23, 1918 California Governor William D. Stephens calls for voluntary mask wearing for all as a way to control the spread. In LA, the mayor and Powers agree it’s a good idea, but the City Council balks. U.S. Surgeon General Rupert Blue telegraphs Powers, asking him not to issue a mandatory mask order.

October 31, 1918 Daily tally of new cases falls below 1,100; Powers prematurely announces that the tide had turned

November 6, 1918 Mount Washington Hotel is converted into convalescent facility for underpriviliged recovering victims

November 7, 1918 The leadership of the Theater Owners’ Association, all wearing masks, appear before the City Council. Arguing that they have been unfairly singled out by having their theaters forcibly closed when other businesses remain open, they advocate enacting more stringent social distancing measures. City Council refers request to Powers, who denies it.

November 9, 1918 Businesses implement staggered hours to reduce street crowding

Mid-November, 1918 New cases drop but still hover around 500 a day; Powers optimistically predicts restrictions will lift in a week. Theater owners team up with the big studios. Together, they appeal directly to the InCuenza Advisory Committee, lobbying for a 5-day total shutdown of Los Angeles, with theaters re-opening for business on the sixth day. Two local merchant organization vigorously oppose this plan, as do Powers and Mayor Woodman.

November 15, 1918 City Council votes 7-2 to approve ?ve-day shutdown followed by lifting the ban on theaters. Powers is against any plan that prematurely lifts bans on theaters. He attempts a voluntary “Stay at Home Week,” which the entire city ignores. Faced with an unexpected late-November spike in flu cases, Powers steps in and the ban stays in place in turn angering the theater owners.

November 29, 1918 New flu cases drop below 350.

December 2, 1918 Powers' request that City Council lift the ban on public gatherings is granted unanimously

December 10, 1918 Flu cases spike again, prompting passagee of quarantine law. Schools close but public gatherings are still allowed

December 12, 1918 A newly-appointed Business Advisory Committee meets with Powers and the Mayor to focus on encouraging the voluntary wearing of flu masks. They intitiate a publicity campaign.

Source: Based on information compiled by Kevin Murphy

This article was printed from https://deadline.com/2020/04/hollywood-coronavirus-impact-